Letter #22

Time traveling down the avenues

Walking around, when I can, on crutches and an air cast has revealed some new truths about my fellow New Yorkers. Namely that a solid half of people are lovely, and want to help. I came down the stairs from my apartment building the other day to find a vision of a young man outfitted in a Buffalo red plaid flannel, oiling down an impressive fawn-colored motorcycle who paused, noted my situation, offered to help me down, and told me how he had been on crutches once while commuting back and forth from New Jersey, and how he learned ultimately that other people were terrible.

And he is correct. The other half are solid assholes, who truly do not appear to even see me, let alone want to hold open a door for your girl. And let me just cast a glaring guilt-inducing glance toward a certain bespectacled father in my building, who instead of holding open a door, asked his four year old if she wanted to wait so she could press a button to buzz herself in, and watched me hobble on precariously through. To men performing fatherhood in public spaces: it’s okay to tell your kids what to do sometimes. In fact, that’s your job. Do better, fathers. In multiple ways.

While incapacitated, too, I’ve done a cursory glance at the single people available in my 8ish mile radius, and have been… disappointed. Didn’t we just survive a plague?Why do you feel like you can ask me for nudes 7 minutes into conversation “because you’re a teacher?” Why are we still posing with photos of My Struggle? But mostly why don’t you have a car, and why don’t you want drive me around in it? I don’t know what I was expecting. Maybe that everything is so precious, and everyone is so strange, why pretend to put your best self forward, why not just surrender? (She says, pantsless, braless, swollen, and dehydrated, raising her cane at the clouds.)

I’m giving the wrong impression. I do miss all of the freaks and the lovers. I cannot wait to revel in the mass of them that will be flooding public spaces, talking to them, making note of their clothes and mannerisms, letting the sun shine on us and laughing unselfconsciously because we’re happy to be here, scuffed up but alive.

:: : :: ::: : :: : : : : : : :: :: : :: : ::: : :: : : : : : : ::: : : :: : : :: : ::: :: : : :: : : : : : : :: : : : : : : : : : : :: : : : : : :

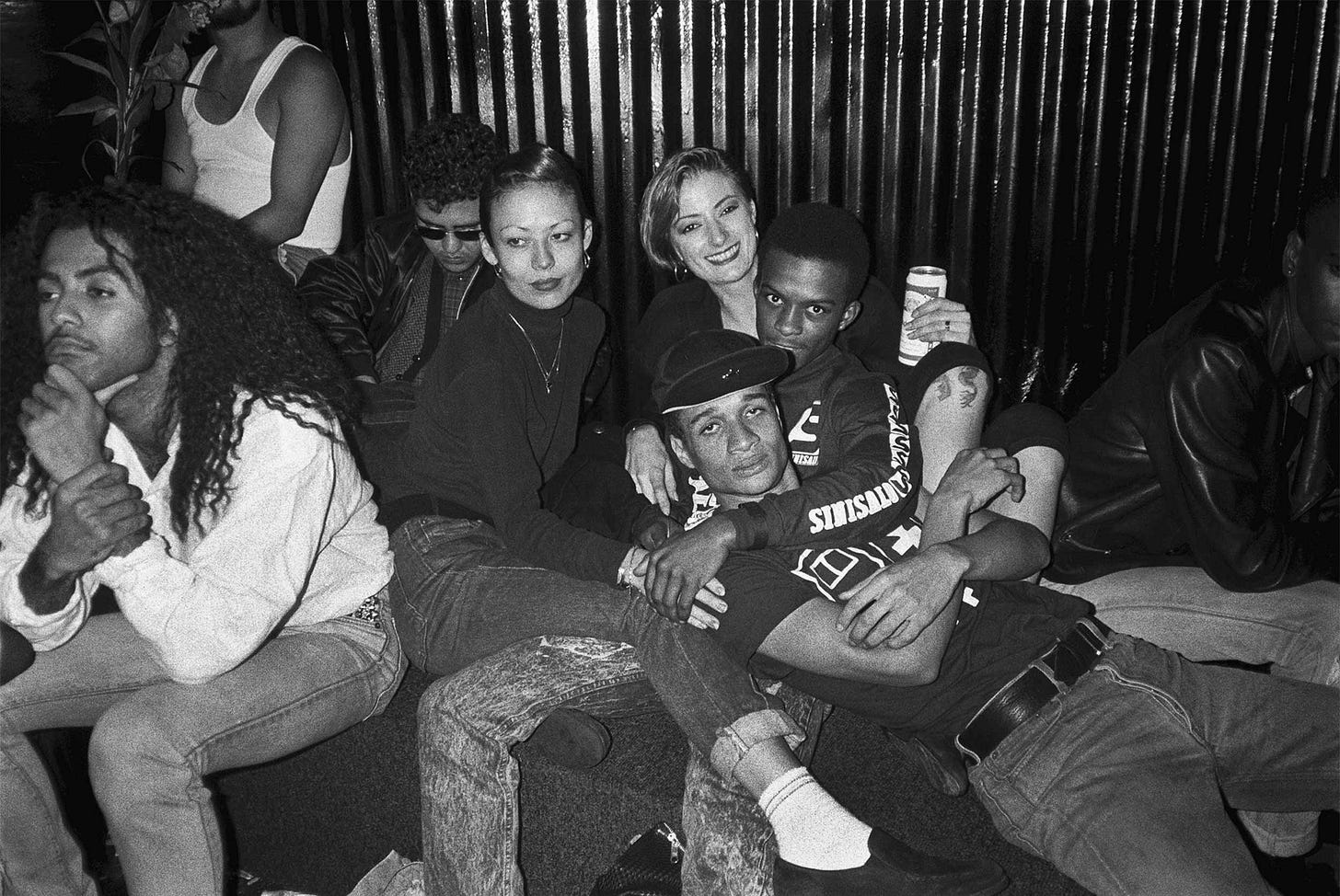

Larry Levan Live at the Paradise Garage Mix

Once commuting home on a Friday evening in the past I overheard two thickly-Brooklyn accented queens reminiscing about the good old days, when they worked a shower curtain factory line by day and then danced at Paradise Garage all night. I imagined them in slick black leather mini skirts and high, high heels, laughing and sweaty under magenta light, and then the methodical motion of their arms in parallel, feeding a lime green vinyl rectangle through a serger, in a line. I play this mix on those Friday afternoons when I taste the air has something sweet to it, and beckoning.

New Yorkers are usually late getting somewhere, hustling our walk a bit to keep up, head down looking at directions or up in the cloud of music in our headphones, fashioning our movie montage as we go. Public objects anchor our glamorously nondescript moments, often unceremoniously tossed away, forgotten, splayed out on the concrete and awaiting more ruin. In Sally’s paintings, these bent, broken, and askew things are in the midst of their own private dramas, unfurling under the light and shadow meant for us in the moments after we’ve overlooked them. I am especially entranced by and keep returning to her recent painting depicting (I think) a bouquet of rolled up grocery store fliers wedged into a steel bannister, abstracted once again from their original anonymity and irrelevance, and given a new grace, in pausing on them to pay attention.

Alma, a drily funny preschool teacher with questionable coping mechanisms gets into a car accident and emerges from a coma with a changed relationship to time. Guided by her quantum physics professor father (played by Bob Odenkirk), who died under mysterious circumstances in her childhood, she explores the new portals she now has access to. The story brings up the big questions that time travel always does — if you go back and do this, it would change this, and this event would no longer mean anything to you, and that would mean that you as you know it are changed, except if there’s fate, which is to say scientifically an infinite amount of fine threads pulling at the fabric of reality, shaping it. Pinning those questions to the even bigger mystery of death give it an emotional weight that matches the gravity of the question. And the rotoscoping animation style makes for an ideal form for the idea — its uncanny lapses allow for moments of time to open up, expand, stretch naturally, as if it’s just a mode of looking we haven’t yet tested. And the performances, especially by Rosa Salazar as Alma, ground it in something even more real, breakable, and breathing.

Real! Housewives! of New! York! City!: Pandemic Edition

… and sometimes you look at people’s trauma blankly and head-on, not through the lens of art at all, just as a voyeur, and because they’re rich and largely morally reprehensible, it’s like candy for the soul.

This one brought me out of my lack of reading spell. The main characters in Yolk, sisters Jayne and June Baek, are also dealing with trauma: June has cancer, and Jayne cannot deal. Despite their archetypes being laid out from the start: responsible, successful June and artsy, brooding Jayne, the sisters subvert and weave in and out of their roles, neither fully comfortable in their own skin or the circumstances at hand. I’m a huge fan of Mary H.K. Choi’s writing, which vacillates between sharp observation and omniscient abstraction and, while comfortingly accurate, never relies on cliche. Her main characters often have the bristling tone of a subtle, stylish girl who says something funny in a circle of people but it’s too quiet, and a bro repeats what she says, and everybody laughs really hard, and she internalizes it forever. (Projection much???) Yolk contains all the elements of an irresistible read: rapid-fire one liners, New York characters and their interior spaces, doubles and mirrors, outfits you’d want to wear, and a complex sisterly relationship that you feel like you’re spying on, heartbreakingly close.

Natalie Bergman, Shine Your Light On Me

Becoming obsessed with a catchy song and playing it constantly on repeat really hits different when the main lyric is Come on shine your light on me, sweet Jesus. And sung by a twiggy blonde woman emulating soul and gospel singers and more than a lick of Lana Del Rey, no less. Am I … singing about Jesus? Repeatedly? On purpose? It feels trippier than drugs to hear my own voice doing that. But I appreciate the devotion. The insistence. And the horniness for holy spirit. Might as well go all in on something, even if it’s the oldest song in the book, or the only city that matters …

Brb, finding the motorcycle guy,

Delighter